That this piece- closest to the real world, of all that I have ever produced- should be about Kashmir, or rather the recent Supreme Court judgment in regards to its status, is ironic. The issues in regards to the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir have much better comprehenders than myself; so much so that any attempt to even talk about the merits of the petition, the contention of the Centre, or the plight of the people may as well be- especially considering the times we live in- nothing short of a measure of blatant disrespect to all those who have poured countless precious hours of their lives listening with ears up to the esteemed, inexhaustible news anchors championing the glorious cause of New Indian journalism. If they can continue to do so, maybe I deserve a chance at this as well. But I’d stray from the judgment itself; a background, mayhaps, is more in order.

I have only once been to Kashmir, but that was at the right time, both in terms of the ongoing affairs, and my age, to have an adequately profound impact on my perspective of the valley to make me write this five years hence. Honesty where it’s due: the ‘impact’ was more of a visual than a political, historical, sociological, communal- pick your intellectual euphemism- nature. Much of my sympathy for the valley, before I developed a keen interest in the history and politics of its turmoils, stemmed from the grace, generosity, and amiability of its (rather politically beleaguered, as I could make out even then) inhabitants, and the serene and picturesque beauty of its landscape.

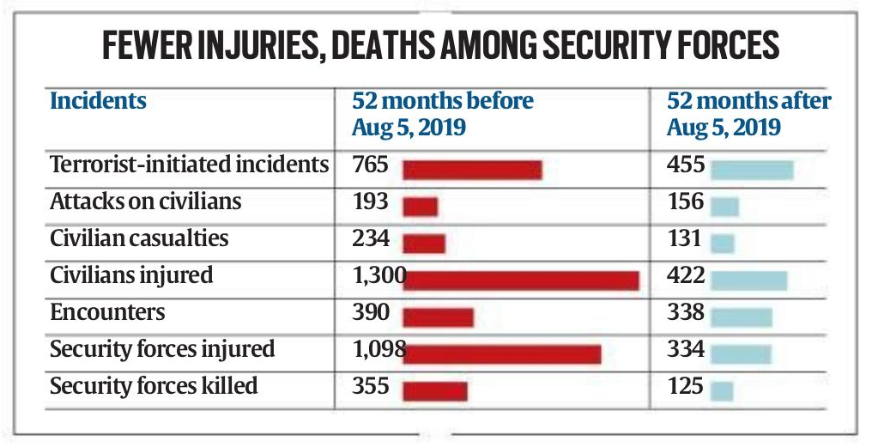

Sipping kahwa on a houseboat boat anchored to the the shallows of the Dal Lake, as I gazed at the peaks far ahead as their tips gradually dawned the shawl of snow, shrouded in the thick evening fog of July, I could only but feel sorry, based upon the stories I was told on the road to Srinagar (most of them true) for what Pakistan’s communal aspirations had done to this place and its people- people who remain there now, and those that had to flee- as I still do. With the brouhaha and rhetoric that accompanied the announcement of the Presidential order abrogating Article 370, one could hope that better days would come. The year 2018 was when I was last in the valley, so I would not know. This data from The Indian Express looks promising, though:

To say that the Article 370 of the Constitution should have been left as it was would be a gross misunderstanding (and underestimation) of the situation that had (to heretics such as myself, now has) engulfed Jammu and Kashmir. I would not deem it appeasement; it is difficult to ascertain who exactly has been appeased, both in the communal context that the current ruling establishment so much likes to champion, and that of the people actually living in the valley. It is to be acknowledged, in my opinion, that the failures of successive governments since 1952 to contain the chimera of Kashmir’s unrest called for a more radical, or rather better-willed attempt to protect the sanctity of the ‘jewel in the crown of secular, democratic India’, as Sumantra Bose put it, in his book Kashmir at the Crossroads: Inside a 21st-Century conflict.

“There is no mantra in which you can put back Article 370”, said the Titular Maharaja of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir (Sadr-i-Riyasat from 1952 to 1965), following the Supreme Court’s judgment. Being the issuer of the proclamation in 1949 that stated that the Constitution of India would prevail over all the other laws of the state, he does well for himself by being right. To look ahead for a smooth, democratic and peaceful ‘integration’- terminology used frequently in the judgment- of Kashmir and Kashmiris into the Union of India is now of paramount importance. Contrary to what the ruling establishment insists on various issues, it is perhaps time to move on from the past, and work towards improving the status quo.

It is true; infamous trends prevalent such as stone pelting, terrorist activities, and kidnappings- under the larger heading of the general insurgency that had gripped the valley since the 1990s- are now at an all time low. The increased usage of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) of 1967 has indeed played a part in the same. However, that the increased number in discretionary (for an act that has Preventive in it, this may be the right word) arrests across the valley- and the country, for that matter- have not lead to, well, an acceptable number of convictions (1218 against 2 between 2019 and 2021, as per the Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs) is concerning, and so are the initial house arrests of political leaders like Omar Abdullah and Mehbooba Mufti.

It is expected that the situation of common Kashmiris on ground may be more woeful- incessant internet shutdowns in the union territory do not help in verifying/nullifying such a claim. It is being asserted by the ruling establishment that all of this comes under the umbrella that is the Centre’s crackdown on all such elements that stoke fire in a place that is colloquially referred to as jannat. To some extent, this can be believed. The reviving tourism industry, along with rising business prospects for non-Kashmiris in the valley- following the allowing of the same to buy land therein- may hint towards a more prosperous future, at least on paper.

The enigma of Kashmir ties together a tapestry of inquiries that have lingered since India gained independence. What defines the essence of a ‘union of states’ within our nation? In our contemporary era, how relevant and workable is the concept of a federal structure? To what extent have communal frictions exacerbated the overarching tumult? How does the Constitution’s design, with a Governor superseding elected representatives, reflect upon the trust in its citizens? And at its core, does the imposition of authoritarian tranquility, under the guise of charismatic leadership, outweigh the potential turmoil stemming from dissent? These questions, entwined within the Kashmir discourse, delve into the essence of governance, trust, and the pursuit of equilibrium within a diverse society.

Considering your thoughtful exploration of Kashmir’s complexities, could you elaborate on your perspective regarding the role of international diplomacy in resolving the longstanding issues in the region, and how it might influence the path toward a democratic and peaceful integration of Kashmir?

As I see it, the abrogation of Article 370 was an attempt by the government to eliminate prospects of international diplomacy interfering in the issues of Kashmir in the first place. Now that Kashmir has lost its special status, one could expect that the internal relationship of India with the union territory will be exempted from external pressures.

Love your thought provoking comment on the removal of Article 370 in Kashmir.

Yes ,the removal of article 370 was a big achievement for BJP and it seems that everything is getting fine over there.

The provision in the article could not have been abrogated as the term of the Jammu and Kashmir constituent Assembly ended in 1957 after it drafted the erstwhile state’s Constitution.

Wanted your newsletter every month!